The Definition of DNA Methylation

Did you know that the amount of cuddles a baby receives from a caregiver could affect the baby’s DNA methylation profile, and in turn, the developmental progress?1 In fact, DNA methylation affects almost every facet of daily life.2 But, what is DNA methylation?

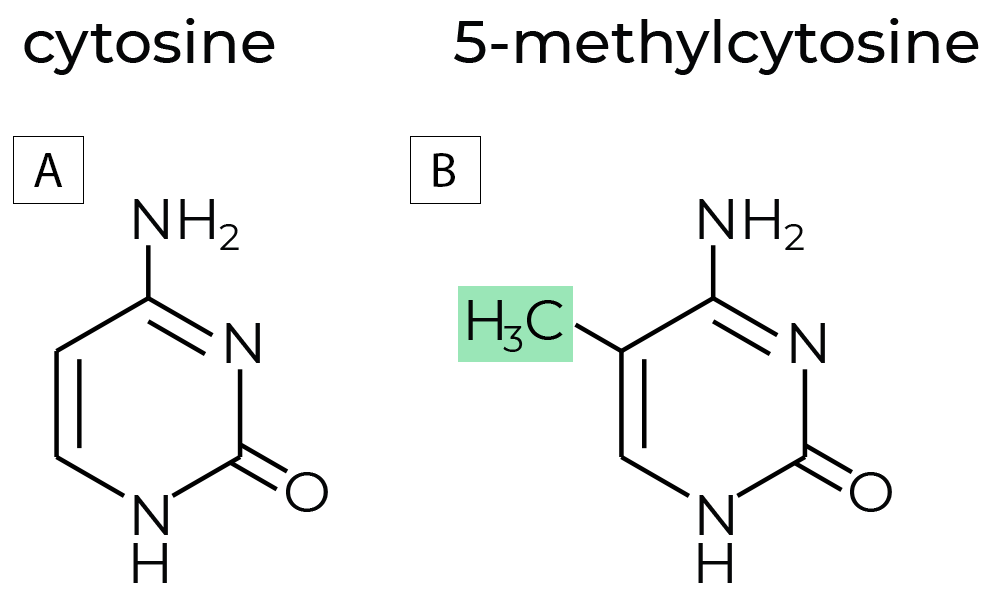

DNA methylation is a chemical modification to DNA molecules. In most cases, DNA methylation refers to the covalent addition of a methyl group to the 5-carbon position of cytosine, forming 5-methylcytosine (5mC).

Figure 1. (A)The chemical structures of non-methylated cytosine, and (B) methylated cytosine commonly referred to as 5-methylcytosine. DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) are enzymes that regulate DNA methylation, which is a key factor in gene expression and chromatin stability. DNA methylation regulates gene expression without changing the sequences of the nucleotides. Hence, DNA methylation is an epigenetic mark, where “epi” implies that this feature is “on top of” genetics playing its roles without alterations in the DNA sequence.

How Does DNA Methylation Affect Gene Expression?

DNA methylation is the most extensively studied epigenetic phenomena, as well as the most naturally occurring.3 In eukaryotes, DNA methylation pervasively occurs at CpG dinucleotides. The patterns of DNA methylation at promoters, gene bodies and enhancers play vital roles in regulating gene expression.4-6 DNA methylation affects gene expression by typically silencing genes through the process of adding methyl groups to specific DNA regions, which prevents transcription factors from binding and accessing the gene, thus inhibiting its transcription and protein production. Essentially, highly methylated DNA is usually associated with decreased gene expression while unmethylated DNA is more readily accessible for transcription.

What Are Commonly Recognized DNA Methylation Patterns?

Some DNA methylation patterns have been widely studied, and researchers have acquired a fair amount of knowledge on their regulation of gene expression. A few examples of such DNA methylation patterns are as follows:

- DNA hypermethylation (substantially increased DNA methylation levels) in promoter regions is generally associated with gene suppression or silencing. A good example is that DNA hypermethylation serves to inactivate the X chromosome and silence repetitive DNA sites.4

- The CpG sites in CpG islands (CGIs - regions with high frequency of GpG sites) associated with the promoters of housekeeping genes and developmental regulatory genes are usually resistant to DNA methylation. However, these promoter CpG Islands were found to be aberrantly hypermethylated in both tumor suppressor genes and DNA mismatch repair genes, which in turn suppress the related genes’ expression. Such aberrant DNA methylation pattern in promoter CGIs is perhaps the most widely studied epigenetic alteration in cancer.5,6

- CpGs in enhancers have been found to contain tissue- or cell type-specific DNA methylation patterns. Such differentially methylated regions (DMRs) may have contributed to the unique gene expression among different tissue and cell types.7

Given that precise gene regulation is important for many fundamental biological processes, DNA methylation is essential throughout organismal development and homeostasis. The applications of DNA methylation assessment vary from cancer, aging, metabolic health to forensic testing.

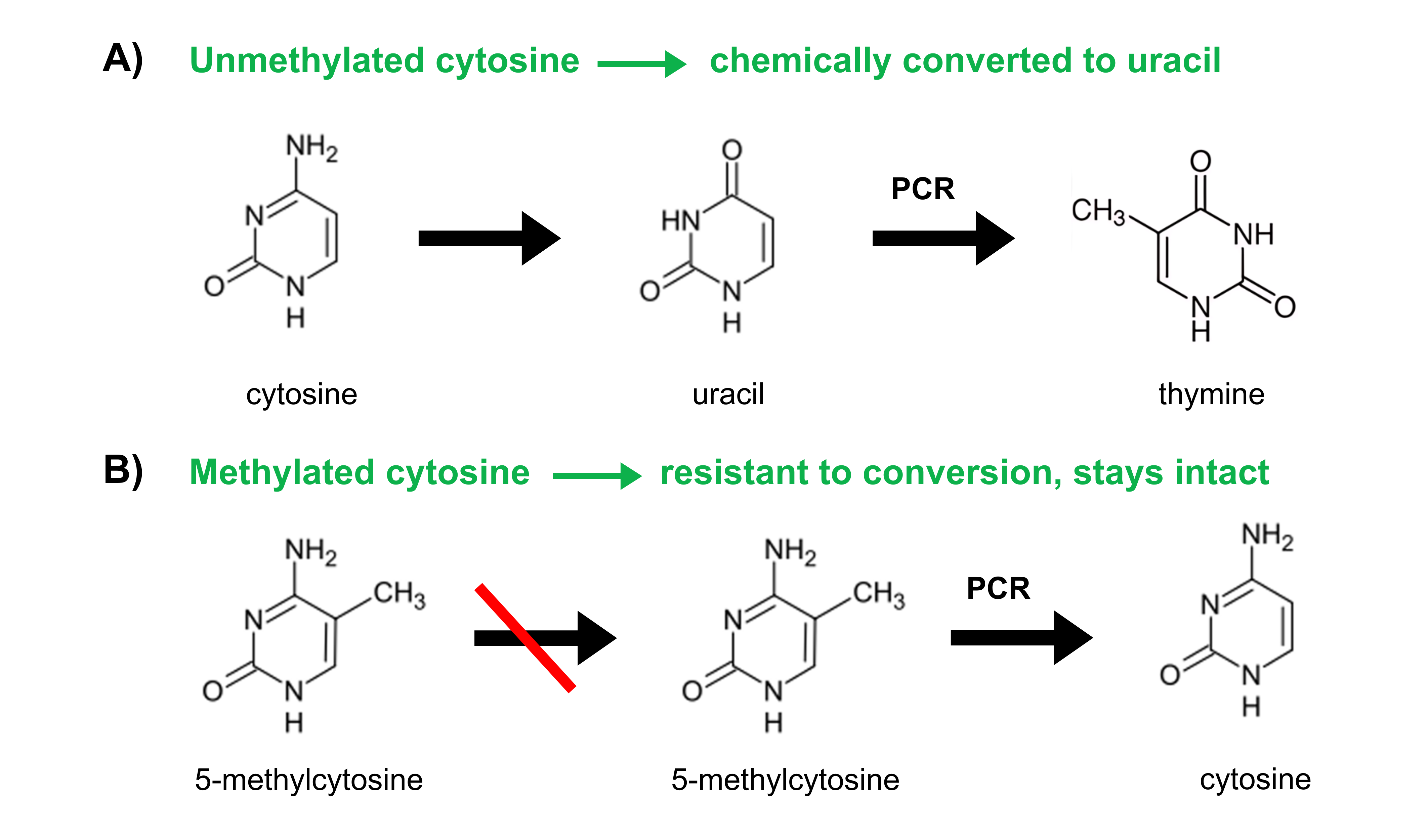

The gold-standard reaction for DNA methylation analysis is called bisulfite conversion. Bisulfite reagents convert unmethylated cytosine residues to uracils (as illustrated in Figure 2) while leaving the methylated ones untouched.

Figure 2. Through the process of bisulfite conversion, bisulfite salts chemically convert (A) unmethylated cytosines into uracils. Subsequent PCR amplification replaces these uracils with thymines. (B) Methylated cytosines, however, are not chemically converted to uracil but are protected and remain as methylated cytosines. Subsequent PCR amplification amplifies methylated cytosines as cytosines.

Many methods have been developed to investigate DNA methylation-based on bisulfite conversion. Since the demand of genome-wide DNA methylation profiling has increased, NGS-based methods have become much more popular.

Choosing The Right Method for DNA Methylation Analysis

Benefits of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

- NGS enables the determination of methylation status at individual CpG sites across the entire genome or in regions of specific interest, providing detailed insights into the methylation landscape

- Produce results with high coverages across an entire genome

- Compatible with any species

Bisulfite sequencing has gained tremendous popularity among researchers for DNA methylation profiling, indicated by the increasing number of related publications over the years. DNA samples that are bisulfite converted must be constructed into libraries that contain adapters for sequencing on a compatible NGS instrument. The methylated cytosines are recognized as “C” in NGS readouts.

Thus far, researchers have implemented a myriad of bisulfite sequencing methods to uncover DNA methylation information for diverse biological questions.

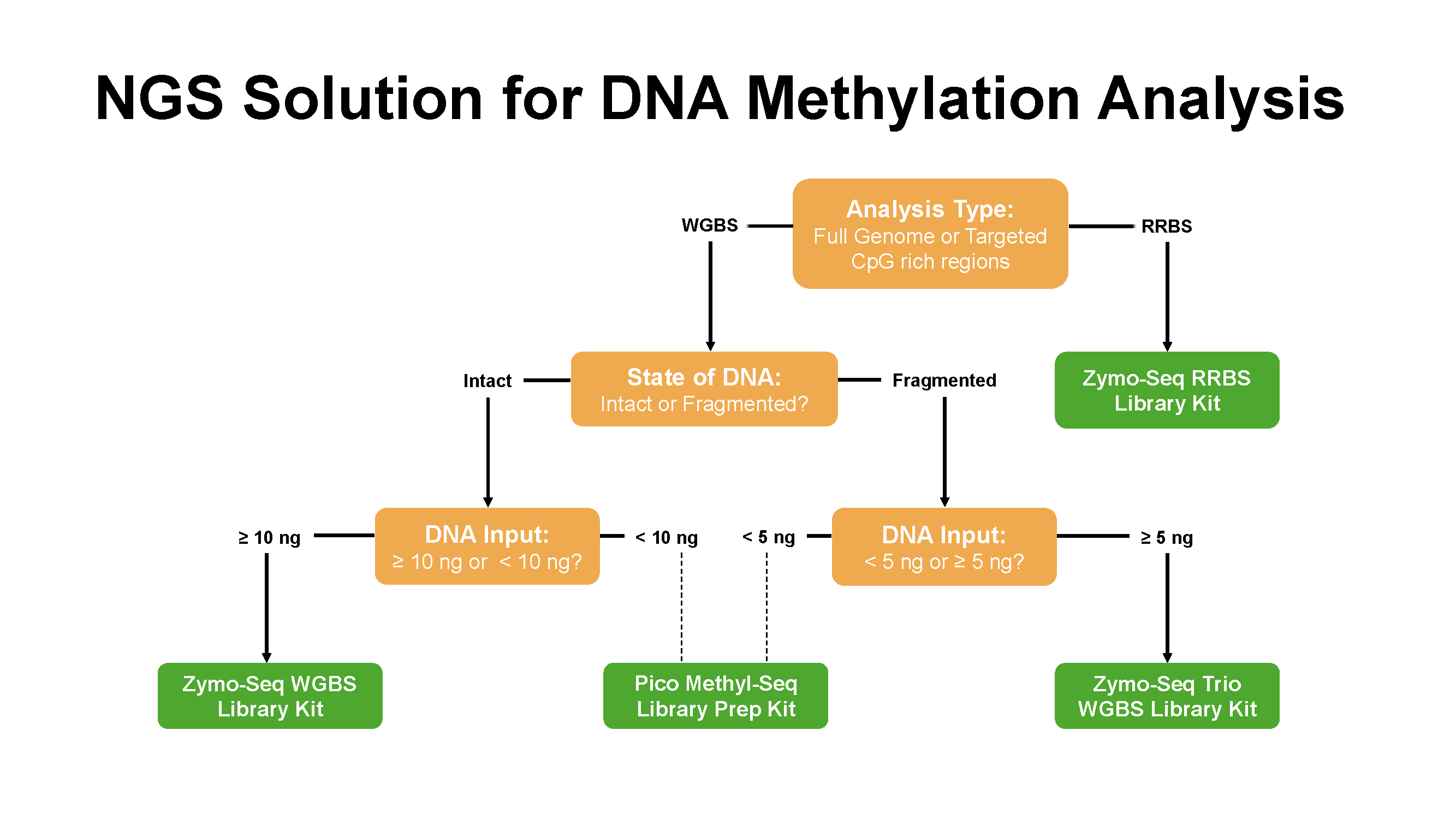

The most extensively used NGS methods include reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS), whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS), and targeted bisulfite sequencing.

These methods share common steps in the procedure of library preparation such as bisulfite conversion, adapter ligation and PCR amplification, but differ slightly at the beginning of the workflows during the preparation of the input DNA materials.

Interested in learning more about these methods, their differences, and which one best suits your research? Select your preferred NGS methods below to find out more!

- Reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS)

- Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS)

- Targeted bisulfite sequencing.

Figure 3. Zymo research offers various NGS solutions for DNA methylation analysis

- Moore, S. R.; McEwen, L. M.; Quirt, J.; Morin, A.; Mah, S. M.; Barr, R. G.; Boyce, W. T.; Kobor, M. S., Epigenetic correlates of neonatal contact in humans. Dev Psychopathol 2017, 29 (5), 1517-1538.

- Huang, H.; Liu, R.; Niu, Q.; Tang, K.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, H.; Chen, K.; Zhu, J. K.; Lang, Z., Global increase in DNA methylation during orange fruit development and ripening. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116 (4), 1430-1436.

- Smith, Z. D.; Meissner, A., DNA methylation: roles in mammalian development. Nat Rev Genet 2013, 14 (3), 204-20.

- Greenberg, M. V. C.; Bourc'his, D., The diverse roles of DNA methylation in mammalian development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2019, 20 (10), 590-607.

- Flavahan, W. A.; Gaskell, E.; Bernstein, B. E., Epigenetic plasticity and the hallmarks of cancer. Science 2017, 357 (6348).

- Ehrlich, M., DNA hypermethylation in disease: mechanisms and clinical relevance. Epigenetics 2019, 14 (12), 1141-1163.

- Song, Y.; van den Berg, P. R.; Markoulaki, S.; Soldner, F.; Dall'Agnese, A.; Henninger, J. E.; Drotar, J.; Rosenau, N.; Cohen, M. A.; Young, R. A.; Semrau, S.; Stelzer, Y.; Jaenisch, R., Dynamic Enhancer DNA Methylation as Basis for Transcriptional and Cellular Heterogeneity of ESCs. Mol Cell 2019, 75 (5), 905-920.